While looking through the bookshelves of a close relative, I discovered a rather significant library of old Mormon books. Most of these books were published from around 1900-1950. As one who loves to read about all things Mormon related, I was the proverbial “kid in a candy shop.” One book that jumped out at me was “A Rational Theology” by John A. Widstoe. The full text of the book can be found here.

While looking through the bookshelves of a close relative, I discovered a rather significant library of old Mormon books. Most of these books were published from around 1900-1950. As one who loves to read about all things Mormon related, I was the proverbial “kid in a candy shop.” One book that jumped out at me was “A Rational Theology” by John A. Widstoe. The full text of the book can be found here.

I’d like to do a series of posts pulling interesting gems from this book and contrasting them with our modern conceptions in the church. Some of this has been done by Matt W. over at New Cool Thang. You can find his various posts here, here, here, and here. I’d like to build on this analysis, and further examine the rational theology Widstoe tries to build up. In this first post, however, I’d like to contrast the type of scholarship that led to such books with the scholarship in the church today.

The Trajectories of Mormon Scholarship

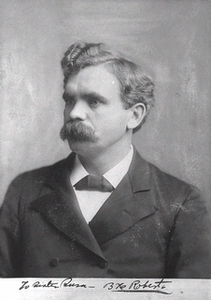

“A Rational Theology” was written during what seems to be the heyday of Mormon intellectual thought. Over at Boap.org, there’s a great post that gives an outline of the time and shows two main schools of intellectual thought that were being developed at the time. The first school of thought, represented by James E. Talmage and Widstoe, attempts to build a Mormon theology from basic principles, coupled with the Bible.  The second school of thought, characterized by B.H. Roberts, relied more heavily on the records of Joseph Smith, and tried to systematize Joseph’s theology, and defend his claims, including The Book of Mormon.

The second school of thought, characterized by B.H. Roberts, relied more heavily on the records of Joseph Smith, and tried to systematize Joseph’s theology, and defend his claims, including The Book of Mormon.

In part due to his relationship with then President Joseph F. Smith, Talmage’s school of thought won out and the “rational” theology became the face of the church’s efforts, including Widstoe’s “A Rational Theology” as the new Sunday School manual. But Roberts’ work was to live on in part thanks to his work on the history of the church. Since then, various influential individuals have augmented these approaches to the church’s theology. Subsequent President Joseph Fielding Smith took the Talmage approach to the extreme, favoring a very literal interpretation, and applying the Bible to many facets of life. Henry Eyring arguably favored a more rigorous scientific approach to knowledge, all while easily (for him) resolving conflict between science and religion, and maintaining his faith in Mormonism. John L. Sorenson dove into the archaeology in Latin America to bolster claims about the historicity of The Book of Mormon.

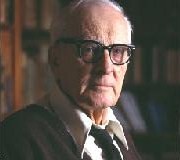

However, it might well be asserted that Hugh Nibley started (or at least popularized) the apologist movement within Mormonism. Attempts up to this point by Talmage, Widstoe, and the like were to build up a theology from scratch, using a few basic principles, and relying much less on the historicity of The Book of Mormon, or even Joseph Smith’s teachings. Nibley’s approach was a reach back in time to the days of Roberts to yank the goal of systematizing Joseph’s work into the late 20th century. Nibley studied everything from Hebrew, to Egyptology, to Islam, to early Christian history. Modern apologists (seem to me) to be more along the vein of Nibley, and they continue to find success, funding, and support from the church both officially and unofficially.

However, it might well be asserted that Hugh Nibley started (or at least popularized) the apologist movement within Mormonism. Attempts up to this point by Talmage, Widstoe, and the like were to build up a theology from scratch, using a few basic principles, and relying much less on the historicity of The Book of Mormon, or even Joseph Smith’s teachings. Nibley’s approach was a reach back in time to the days of Roberts to yank the goal of systematizing Joseph’s work into the late 20th century. Nibley studied everything from Hebrew, to Egyptology, to Islam, to early Christian history. Modern apologists (seem to me) to be more along the vein of Nibley, and they continue to find success, funding, and support from the church both officially and unofficially.

Scientists and Apologists

I’m interested in the contrast between the Talmage/Widstoe method, and the current apologist method as inspired by Roberts, and most recently, Nibley. Both methods are an attempt at an intellectual justification for Mormonism (or at least parts of it). Talmage/Widstoe addressed Mormon theology as a whole, relying little on Joseph’s cosmology, idealistically asserting that, in time, the LDS Church would embrace all truth. Roberts/Nibley became defenders of Joseph’s claims, charting a rational walk through the apparent irrationality of The Book of Mormon, priesthood, revelations, etc. However, even so, for those who have tried to tie Joseph’s cosmology together, the task is daunting. Contradictions appear, and Joseph himself was learning line upon line, sometimes later ideas casting confusion on what previous claims were intended to mean.

The Talmage/Widstoe method appears to be more insulated from the truth claims of the church, relying more completely on logical reasoning, and small assertions to take us to the next reasonable step. Moreover, the works of these two individuals are very academic, citing hundreds of books, research, and other well verified material. This perhaps gives their points of view more credibility.

Current apologists attempt to apply logical thinking and reasoning to their (Joseph’s or the church’s) claims, but admittedly, they are doing most of the work themselves (it’s not a mystery why most apologist papers on the historicity of The Book of Mormon reference Sorenson’s work). There is much less scholarship on Mormonism outside of the church, whereas Talmage/Widstoe could build on basic theological principles, hundreds of years of philosophical thought, as well as hundreds of years of research on the Bible and its manuscripts.

When I look around at the current Church landscape, it appears that the attempt at rationally building a theology from scratch has all but gone away. I don’t see any new books at Deseret Book that attempt to describe the Gospel in this way, and indeed the church does not produce manuals that aspire to such a lofty goal.[1] On the other hand, I do see plenty of apologist books, articles, and institutions dedicated to defending Joseph’s claims, The Book of Mormon, The Pearl of Great Price, Joseph’s revelations, etc. In fact, we even saw a talk in general conference in October that had a familiar apologist ring to it.

So what think ye? Are the rational theologians in Mormonism dead? Are apologists the new rational theologians, or do they have a different goal in mind? Is a rational theology realizable, and should we try to find it, or should we accept things purely on faith? Or should we seek for both? And where do we draw the line?

[1] In all fairness I have to give credit to Blake Ostler who absolutely attempts to provide a “rational theology” in the context of Mormonism. Although his work is not endorsed by the Church, or sold at Deseret Book.

Comments 57

I am certainly not an expert on this issue but I think it might mis-leading to suggest that Widtsoe and Talmage did not try to use JS, like Roberts did. I think that what is significant about their two apporaches is the way they conceive God. Widtsoe etc. saw God as an intelligent being (a mind – to use the phrase from the Correlation posts at BCC) while Roberts seems to have focussed on a more embodied theology. In this case I think that Nibley’s contribution was actually more in line with Widtsoe et al. because of the focus on a historically singular pattern of religious practice which Mormonism is the apotheosis of. This is an emphasis on mind as well. Though I think that Nibley took issues of materiality seriously, but most often in regards to the environment. I think therefore that Nibley and modern-day apologists are still trying to fit Mormonism within Academia and defned it to the academy rather than trying to generate a new speculatively embodied theology (which I think is the Roberts/Young/Smith legacy).

I agree, current apologists are brain dead morons. BTW, I’m not being snarky, I truly believe it.

How does Orson Pratt fit in this equation? He was the Church’s first scientist and Academic.

Author

Re #1 Aaron

I am definitely not an expert either. I hope I wasn’t suggesting that Widtsoe and Talmage did not try to use JS at all. That was not my intent. They certainly did use JS’s ideas. But it is the method that differs in my mind.

So it sounds like you’re suggesting the opposite of what I’m suggesting – that Nibley and modern day apologists are following the legacies of Widstoe/Talmage? Perhaps you’re right.

I think the primary difference is that modern day apologists/Nibley know the truth (the current truth claims of the church) and try to defend it, perhaps sometimes shoe-horning a theology into Mormonism. Talmage/Widstoe believed in a rich theology that would receive all truth, and tried to build one from the ground-up, perhaps sometimes shoe-horning their theology into Mormonism. So I see Nibley and modern day apologists trying to defend Mormonism/truth to the academy, and Widstoe/Talmage presenting an entirely new system that sought truth to the academy for their consideration.

In other words, I think what is significant is the way in which they approach Joseph’s (and the church’s) truth claims, not necessarily the way they conceive God. But again, I’m not an expert, and while I have read many FARMS articles, I have not read a lot of Nibley’s work.

Author

Re #3 Jeff

Good question. I had actually not considered this. From what I know of Pratt, I would have considered him in the same vein as Talmage/Widstoe. But I would love to have someone who really knows offer an opinion.

I think the difference between the two also explained the predominance of the apologist approach. The more “scientific” approach (although also incorporating philosophy, history, archeology, etc.) tends to follow the evidence and see where it leads. This will sometimes be at odds with traditional interpretations of the gospel. This can also cause conflicts. A well-documented example of this is Galileo. Eventually, the heliocentric model prevailed, and the church still lived through it. It ended up being a “tradition” they were clinging to and not “truth”.

The LDS Church clamped down on this quite a bit. J Fielding Smith denounced evolution as a tool of Satan. BRM had a fairly anti-scientific bent when anything even remotely encroached on his interpretations of what “was”. Historians were excommunicated. We heard talks about not teaching something because it’s true, but only if it’s faith promoting.

The natural result of this is that it’s only “safe” to be an apologist.

I just dusted off and read a Deseret Book-published book from 1959, Lowell Bennion’s Religion and the Pursuit of Truth. I can’t conceive of something similar being published by Deseret today. Though intended for a popular audience, it went into great detail in analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of the various methods of gaining knowledge — authority, philosophy, practical experience, empirical science, religion, and faith. (Has anything published by Deseret recently included the phrase “das Ding an sich?”)

The book made no effort at all to defend the singular truth claims of Mormonism, like the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, but essentially deemed them authentic and emphasized living the principles they contained. I was struck by a statement that when empirical knowledge is available, it is preferable to “faith” — an echo of Stephen Jay Gould’s concept of the “non-overlapping magisteria,” or the complementary, exclusive respective provinces of empiricism and faith.

I would classify this book as more in the Talmage/Widsoe tradition — a setting of Mormon faith and life within the larger context of religion generally, with far less emphasis on its status as the exclusive Kingdom of God. So the tradition was still alive, well, and thought well enough of by the Church institution to be published by Deseret Book as late as 1959. The shift towards an emphasis on fortifying the Church’s singular truth claims and exclusive authority came later. I wonder when, exactly, and what was the catalyst?

I consider myself an apologist, but I think that you will find a variety of beliefs on a great many subjects among apologists at FAIR and FARMS. It is true that the Mesoamerican theory dominates the intellectual apologists of the Church as far as Book of Mormon lands go, as does the notion that we have a missing papyrus for the Book of Abraham. Some apologists try to make this or that artifact into something the Book of Mormon describes, such as a species of deer into a horse, or an obsidian bladed weapon into a “steel sword.” I on the other hand am perfectly comfortable that the Book of Mormon says precisely what it says, and there are just a great many things that we haven’t found yet. Too often people focus too much on what hasn’t been found yet, and forget about the great amount of things that have been found.

So I would say that there are popular paradigms among apologists, but some like me are not into the popular paradigms. I do not believe in a missing papyrus for the Book of Abraham. I do not believe that Cumorah was in Mesoamerica. I seek for a rational theology, but not necessarily in terms of popularity of a theory among apologists. I believe in eclecticism, because, as a martial artist, I follow Bruce Lee’s worldview, that things are only good on their own merits, not because of tradition or popularity. I will follow a popular theory only if it is the most rational, not because John Sorenson or Hugh Nibley or John Gee said it. And I mince no words when I reject a popular theory, probably being too abrasive.

And furthermore, I don’t like the word belief when it comes to things that aren’t revealed plainly. I end up changing my mind too often on things to be committed to anything that I think at any point in time. This doesn’t mean that I change my mind on the core of my testimony. It just means that I have things that are at my core that I “know” by the spirit, and other things that I just “think” that will change tomorrow.

But I think that your “schools of thought” notion is a bit flawed, because it really was Joseph Fielding Smith, Bruce R. McConkie and Mark E. Peterson championing absolute scriptural literalism and condemning harmonization of science and religion, while the other earlier brethren like David O. McKay, Widtsoe and Talmage were really after finding a true harmony between science and the scriptures. So I think you have it a bit wrong on who was on the different sides of what, and what the real issues at hand were between these schools of thought. Joseph Fielding Smith was concerned with orthodoxy and preservation of traditions to the extreme denial of all science, not rationality.

Oh and one more thing. If you are defining rational theology as primarily building a theology from scratch, I don’t think that is necessarily always rational. Applying skepticism and critical thought to already existing ideas and throwing things out that aren’t rational is actually a better manifestation of rationality. There is no need to throw the baby out with the bathwater when you already have good ideas that make sense.

RE: #7 Thomas

“The shift towards an emphasis on fortifying the Church’s singular truth claims and exclusive authority came later. I wonder when, exactly, and what was the catalyst?”

I would guess when Leonard Arrington was chuch historian with the increase in scholarship, faithful and otherwise. People realized that there were too many things that had been taken for granted and needed explaining.

“So what think ye? Are the rational theologians in Mormonism dead? Are apologists the new rational theologians, or do they have a different goal in mind? Is a rational theology realizable, and should we try to find it, or should we accept things purely on faith? Or should we seek for both? And where do we draw the line?”

When you talk about rational theology and theologians. Are you really taking about theology or are you talking about a project to describe Mormon doctrine as rational? I think there is a big difference between the two, but I want to make sure I understand what you are getting at.

I think the apologists are trying to come up with what they consider to be rational descriptions for what is found in the BOM but from what I think of as a theological point of view their work is not interesting. But what I am calling a theological point of view concerns itself with interpretation of scriptures, and the intellectual / spiritual tradition of Mormon thought and Christianity. Its not interested in proving anything to be true, but rather finding lessons, problems, questions, areas of exploration and so on, in the religion and bringing them to bare on our spiritual lives. The only Mormon I am aware of who is really doing this these days is Bob Rees.

As someone with an Academic background who converted to the church in adulthood, I am never sure what to make of so called Mormon scholarship. The projects of folks like Widstoe, Nibley, and the apologists are so foreign, and the writing is always so self limiting. I don’t know, maybe you need to be a lifer to understand why anyone would want to do what they do / did.

Re #8 SkepticTheist

I actually agree completely. I’m not sure where I was saying otherwise. Perhaps in saying that JFS took Talmage to the extreme. Hmmm, in looking over it, that isn’t what I meant to say. Yes, you’re right, and this point is exactly what I was trying to say.

Yes, I meant it in the way that the book “A Rational Theology” is laid out. I agree that skepticism is good in the context you’ve said, but there is certainly value in laying a firm foundation based on well reasoned logic. This is exactly what many great philosophers have done.

Re 11 Hunter

Yes, I am merely talking about the “rational theology” laid out in this particular book.

Yes, and in this context, I’m not sure what to make of scientists like Widstoe. Clearly he was interested in Mormonism being true, but I don’t get the impression that he was a typical apologist. This is part of what I’m trying to explore. In a sense, I think Widstoe/Talmage were in fact trying to find lessons, questions, and encompass all truth with their theology built from the ground up. But I do see your distinction.

Could you expand on this? I am definitely an academic as well (though in a completely different field than this), and I find most apologist writing to be self-defeating as well. But I get a different feel when I read Widstoe/Talmage. I wouldn’t classify Widstoe and Nibley the same which is sort of the distinction I’m trying to make.

Where would you put Ostler’s effort in this schema of seemingly conflicting efforts at theology/apologia?

I think Mike S nailed it in #6. (Perhaps I liked his comment because Galileo is one of my favorite heretics, and my avatar on my blog.) The reason why apologists seem to have the upper hand over rational theologians right now is because it’s only “safe” to be an apologist. There does seem to have been a bit of a purge among intellectuals. I think there has been a relaxation in recent years, but I don’t yet feel it is safe to express scientific, faith-neutral (as opposed to faith promoting) points of view in a church setting. I’m glad that people like Bushman and Sorenson are making it safer, and I hope the trend continues, but I’m not convinced rational theology won’t cycle back to being thought of as faithless.

MH, hows it going?

I don’t see faith promoting and faith neutral as being the same thing. Skepticism and critical thinking are things that help us avoid gullibility, or faith in incorrect/false things. If something is not correct, then promotion of correct faith is apologetics faced in the right direction, and skepticism of that which is false. Therefore correct promotion of faith is apologetics that promote correct thinking, and therefore skepticism aimed at that which is false. Therefore, as a skeptic, I’m an apologist for that which is correct, and a skeptic and debunker of that which is incorrect, all at the same time. And as your friendly neighborhood apologist/skeptic, I’d like to debunk the idea right now that promotion of a “faith neutral” attitude is gullibility that leads to incorrect thinking. Rather, we must have the attitude to promote faith in the right direction at all times, and choose to have faith. If that means debunking incorrect traditions that are not rational, that is what it means. If it means debunking new popular theories that are not rational in favor of tradition that is correct, then so be it.

I think anyone who is going to talk about Nibley needs to start with Approaching Zion. Nibley, when he wasn’t preaching repentance was exploring in context, not engaging in apologetic discourse. There is a big difference. Now his explorations can be used for apologetic work, but all of his apologetic work can be found in one volume and he had a positive distaste for it.

I really think the new model is more exploring in the broader context.

That’s a great question. I will have to cede ignorance on the issue. I have only recently been exposed to Ostler’s work and have yet to read his stuff. I do realize that he tries to ground Mormonism in philosophical thought, and I know he tries to expand on the notion of God. But again, I’m ignorant on this.

Blake, care to comment and tell us where you see yourself?

One thing to remember is that Widtsoe originally had much of Roberts theology in his book, as he was quite the follower of it, but much was edited out by other apostles (though it’s still mainly there). Widtsoe was a strong supporter of Roberts, so to put him on the opposite of a Talmage/Roberts Dichotomy seems incorrect. If any thing, Widtsoe is the bridge between Talmage and Roberts that made both their viewpoints work together.

Great post, and lots to think about. I don’t claim expertise in all the authors listed, so I won’t hazard a guess on things I don’t know. But I do see the trend that’s being discussed that favors apologists over scientists. And perhaps that makes sense in the context of a church meeting; but published works can and should show a wider diversity of thought. I’m with Douglas Hunter – sometimes I have read things that others have suggested were scholarly (LDS scholars) and wondered how that qualification was made given the very limited scope of their thinking. To me, real scholarship follows the evidence where it leads. I realize that even scientists are sometimes prone to ignor the evidence that doesn’t fit their theories, but Mormon theology with Mormonism as the beginning and end is too narrow to be scholarship, IMO. Yet, I firmly believe that there are scholars and scientists in Mormonism who are simply on the downlow. There were so many of them when I was at BYU – open minded, exploring types who really wanted to ponder truth. Then September Six happened. While I didn’t know any of those directly impacted by September Six, all of Mormon scholarship was indirectly impacted. When you outlaw free speech, people go underground until it’s safe to come out into the light again. Yet, it’s quite clear that there are those, even in the 12, who are scientific minded rather than apologetics-minded.

“yes, and in this context, I’m not sure what to make of scientists like Widstoe. Clearly he was interested in Mormonism being true, but I don’t get the impression that he was a typical apologist. This is part of what I’m trying to explore. In a sense, I think Widstoe/Talmage were in fact trying to find lessons, questions, and encompass all truth with their theology built from the ground up. But I do see your distinction. . . I find most apologist writing to be self-defeating as well. But I get a different feel when I read Widstoe/Talmage. I wouldn’t classify Widstoe and Nibley the same which is sort of the distinction I’m trying to make.”

I get where you are coming from, and I think the distinction you are making has merit. there does seem to have been a significant change across the 20th century in how the project of examining doctrine in light of current scientific thought is undertaken, even if one thinks its a bad project, it seems to have changed with current apologetics being the most disappointing.

The thing that makes me uncomfortable with that project in all the various forms I have been exposed to is that it doesn’t really do a good job of exploring the potential problems inherent in applying the idea of rationalism to doctrine (I mean this very broadly). Why should science and church doctrine have anything to say to each other in the first place? These are radically different ways of describing the world, and as I understand them they are trying to describe very different things in very different ways. They are totally different projects.

I am also very uncomfortable with how science is represented. I have done some science and I know many folks who do science for a living. The common trait I see is that the defining characteristic of people doing scientific research is that they are always at the limit of their knowledge, formulating new questions and trying to figure out if they can even be answered and if so, how? So my experience of science is one where the epistemological threshold is always right there in your face, showing you vast areas of which you know little or nothing about. I think that people who talk about science in the context of doctrine are often trying to make science about some sort of absolutes, a set of epistemological certainties.

To Hawk’s point about the 6. It seems that since the 90’s (and probably earlier) the church is in the very strange position of trying to be strongly pro-education while at the same time being strongly anti-intellectual. I think this is part of the reason our church manuals look the way they do. Lost of encouragement to learn, but continually repeating the same info.

I think of it more in the practical sense than in the sinister. As the church grew and grows, there is a need to develop and maintain a single catechism easily taught and transmitted in multiple languages. And while scholarship still goes on, it has certainly retreated from days gone by.

And there have been and are some GAs that are bent on cracking down on those that might expound a different view. But because the gospel has been so refined over the past 75 years, is there an on-going need for a Talmadge/Widsoe, et al type of analysis and rationalization? In the mind of the church leadership, I’d say not. But there is still plenty of intellectualism applied to the Gospel, just not in quite the rebellious ways of 10/15 years ago.

In the minds of many the aim of some new scholarship has been to tear down the Church rather than build it up.

SkepticTheist,

I don’t see faith promoting and faith neutral as being the same thing. I don’t either, which is why I said “faith-neutral (as opposed to faith promoting).” Elder Oaks and Elder Packer have both said variations of “just because something is true doesn’t mean it is useful.” I get that. As you said, “correct promotion of faith is apologetics that promote correct thinking”. I agree with you. Oaks and Packer are in the business of faith promoting–they don’t like anything faith neutral because it is too close to faith destroying for some people.

I like your idea of correct thinking as the correct purpose of apologetics, but I’m not so sure that Packer and Oaks are real comfortable with this correct thinking because in some cases, it might not be faith-promoting. For example, Bushman talks about Joseph’s treasure digging. I found it helpful to my faith to understand the context of Joseph’s life. Others found his treasure digging the faith destroying. I’d call Bushman’s books faith-neutral, and I think Oaks and Packer are probably uncomfortable with Bushman, because not everything Bushman says is faith promoting. I see Bushman as more of a rational theologian whereas Oaks and Packer are more apologists. If we use JMB’s definition of apologist, rather than SkepticTheists’s definition, it appears that apologists in our church don’t like rational thinkers, and in the 1990’s were out to purge rational thinkers that they found faith destroying. Perhaps some of these people were faith destroyers, but I believe many of them were merely rational thinkers.

Douglas Hunter, I think you’ve stated the difference and limitations of science and religion quite well. I wish the church would add a bit of rational thinking to the manuals rather than repeating the same thing over and over.

Modern apologists have more in common with defense attorneys than with scientists. Hence the name. Their mission seems to be to defend against criticism of the status quo by any argumentative means necessary, leaving us with a little less knowledge than we started with. Example: Criticism: The reference to horses in the Book of Mormon is anachronistic. Apology: Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence (not true, BTW); there’s evidence for horses you didn’t know about; the Book of Mormon word for horse doesn’t necessarily mean horse anyway. So from the apologist we learn that a) lack of evidence doesn’t prove anything, b) there is evidence, and c) the Book of Mormon doesn’t claim anything supported by that evidence. Nice debating tactic, but not terribly informative.

The common apologetic technique of reinterpreting revelation and doctrine until it fits whatever evidence is available has the collateral effect of undermining confidence in any interpretation. It’s a slippery slope to doctrinal nihilism.

“In the minds of many the aim of some new scholarship has been to tear down the Church rather than build it up.”

Based on my limited knowledge I would say that, this has been a fairly common idea for a long time (30 years++). There seems to be a type of thinking in the church that believes questions are all bad, exploration is all bad, and so on. I think we are all aware of the authoritarian tendency in the church that tries to limit interpretation and the possibilities of doctrine / theology. That tries to keep members focused on received meanings and proof texting, over reading scriptures for the sake of developing interpretations and seeking meaning.

There is still a lot of educating to be done. Unfortunately its not common knowledge that there are a vast array of worth while and challenging questions that seek to expand our understanding and refine our practice. Not all questions seek to call into question the faith of believers – That should be self evident but its often not.

“But there is still plenty of intellectualism applied to the Gospel, just not in quite the rebellious ways of 10/15 years ago.”

I think “rebellious” is a poor fit in some cases. Since having met some of these folks and knowing their work, the label rebellious misrepresent what they were trying to achieve.

What is intellectualism?

Thanks MH.

When I look at how FARMS developed from a table in the corner of Professor Welch’s office, and before that, from his interest and exploration of the gospel and Don Norton’s collection of photocopies of essays for understanding the temple better, I look at people interested in the intellectual exploration of the gospel and eternal themes.

That community has never failed or gone away or been stilled.

Re #20 Douglas

I like this, and this is how I view it too. But it is too idealistic in the real world. When JFS interprets Genesis to imply that the church is 6000-7000 years old, he has stepped on the toes of science. That is undeniable. The problem is that, as you went on to say, science is on the forefront of epistemology, trying to makes sense of that which was incomprehensible. As a result, JFS may not have realized he was stepping on the toes of science (though I admit I find this hard to believe since Henry Eyring certainly knew a 6000 year old earth was unrealistic). But the point is, as science grows, it touches areas previously thought to be the domain of religion. In my own life I handle this as I see fit, but for many, this will shrink their view of religion which is unacceptable.

Re Matt W.

Hey, thanks for stopping by! You make a good point here. Perhaps I am manifesting my ignorance of the real history. I tried to do my homework, but maybe I didn’t do a good enough job. Thanks for pointing this out.

“When JFS interprets Genesis to imply that the church is 6000-7000 years old, he has stepped on the toes of science. That is undeniable.”

I don’t know if I would call that stepping on the toes of science, but he was definitely stepping on the toes of scriptures! For me that’s the important thing. Science as a field is totally unaffected by his belief in a “young earth” But our religion and the institutional / cultural / doctrinal expectations that follow from a president of the church doing something like that have a long lasting impact. The fact that evolution, or a world wide flood are still issues of debate in Mormon circles is tragic proof of this. Scriptures has been misread and misunderstood and made religion something that it never intended to be.

“But the point is, as science grows, it touches areas previously thought to be the domain of religion.”

I see this as a result of not taking religion seriously as religion, it follows from not asking questions about how rationalism and theology-doctrine-religion interact.

##21 and 24 re: “rebelliousness” and “tearing down” — You say “rebellious” like it’s a bad thing. And yet darn near every Mormon house has Arnold Friberg’s painting of a notorious rebel kneeling in the snow next to his horse at Valley Forge.

Mormons’ faith that their leaders receive a uniquely clear kind of inspiration, such that they should be expected to know the will of the Lord better than anyone else, does put restraints on their contradicting their leaders, as do (arguably) certain temple covenants. (I’m not sure speaking the truth, out of unalloyed love of truth, ever counts as “evil speaking.”)

And yet even with that inspiration, the Brethren get things wrong. Moreover, they do on occasion — quietly — take the measure of the ordinary Saints’ thinking, and adapt accordingly. There is a school of thought that holds (as per Elder McConkie’s letter to Eugene England), that it is the province of the most self-confident of the Brethren to state the doctrine of the Church, and that it is everyone else’s duty to echo what they say or remain silent. We ought to obey God rather than men. While charity, friendship, loyalty, and concern for the Church’s overall welfare are among our religious duties, our first duty is to the God of truth. Sometimes that duty has to prevail.

I recall reading that in ancient China, there was a tradition that a bureaucrat who objected to imperial policy had the right to send a memo to the Emperor — but there was a catch. To cut down the possibility of backbiting, fault-finding, and influence-seeking by self-serving dissent, the guy writing the memo had to kill himself after sending it. We may not want to go quite that far, but there’s something to be said for giving the Brethren a wide margin for harmless error, and allow a large safety margin for our own likelihood to disagree with leaders for the wrong reasons. But in the end, we are accountable before God for how faithful we are to the light and knowledge we receive, and if our duly designated leaders tell us to do a duty we simply can’t reconcile with righteousness, I believe we are accountable if we ignore our conscience and just fire away with everybody else.

Much of the “rebelliousness” of past Mormon scholarship was rebellion against the perpetuation of an objectively false narrative about the Church, and the elevation of institutional loyalty to a priority over other considerations that reasonable, faithful people could find improper. Rebutting the errors in a book presumptuously entitled Mormon Doctrine isn’t tearing down the Church — it’s refusing to yield the field to a good man who acted ultra vires on the occasion of its publishing. Liber Mormonae doctrinae delenda est.

MH,

You say:

“I like your idea of correct thinking as the correct purpose of apologetics, but I’m not so sure that Packer and Oaks are real comfortable with this correct thinking because in some cases, it might not be faith-promoting. For example, Bushman talks about Joseph’s treasure digging. I found it helpful to my faith to understand the context of Joseph’s life. Others found his treasure digging the faith destroying. I’d call Bushman’s books faith-neutral, and I think Oaks and Packer are probably uncomfortable with Bushman, because not everything Bushman says is faith promoting. I see Bushman as more of a rational theologian whereas Oaks and Packer are more apologists. If we use JMB’s definition of apologist, rather than SkepticTheists’s definition, it appears that apologists in our church don’t like rational thinkers, and in the 1990’s were out to purge rational thinkers that they found faith destroying. Perhaps some of these people were faith destroyers, but I believe many of them were merely rational thinkers.”

My reply:

That is not how I see it at all. There is a movement towards rationality in apologetics while maintaining an unwaivering faith. Bushman is not faith neutral at all. Bushman is trying to REDEFINE faith, thereby preserving it, taking into account REAL FACTS. If we go back to the notion promoted in this post to the beginning of starting from scratch with theology, that makes sense only when a belief is not in line with facts. I see naive apologists as people who ONLY want to preserve faith at all costs to the detriment of rationality by preserving traditions that need to go, like young earth creationism and no death before Adam, and no pre Adamites.

I see true apologetics as a much more complex and paradoxical than that. I think that the types that Elders Oaks and Packer typify are starting to step back and are realizing that they need heavyweights to come in to re-define theology. The problem I see is that where established paradigms are in place among the rationalists that need to go, those things are going to be more die-hard. The missing papyrus theory and the Kirtland Egyptian Papers issue is the one that is one bone that I pick a lot. Evidence shows that Joseph Smith had in mind a translation from the Sensen Papyrus that is not an Egyptological translation. Period. FARMS would have us believe that it is not a rational proposition. Brian Hauglid says the papyrus has been translated, and just doesn’t translate that way. Therefore we have a missing part of the Hor Papyrus containing the missing text of the Book of Abraham. To them, that is the only rational way out. The problem is, Facsimile #3 also manifests the same exact problem, but in this case, we have unambiguous translation of the names of the individuals above by Joseph Smith, and an Egyptological translation does not match. The only rational explanation left for apologists is that it is not an Egyptological translation that Joseph Smith was doing. Now we just have to figure out what he was doing. This is in line with rationality and the facts. Just because we see that he was doing something that we don’t understand yet doesn’t mean that there isn’t a rational, faith building explanation to be found. But that explanation MUST emerge from starting out with the facts of the matter and rationality, and not evading the issue by saying that we have a missing paypyrus. We may well have missing portions, but in reality, the key portions that we have are not missing. Now we must figure out how to explain it. That is all. Not say, oh we have a missing papyrus, end of story, and then pass of the responsibility for the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar on Joseph Smith’s scribes. If they spent the same amount of time and effort on the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar translations of the Sensen Papyrus that Hugh Nibley has on Facsimile #2 and its explanation which resulted in a six hundred page volume posthumously published as One Eternal Round, we could actually get somewhere and have a more rational explanation for what we see in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar. As it stands now, the anti-Mormons have the upper hand, only because the apologists have focused on where the most fertile ground is, and have not dealt with the real “icky” stuff where the greatest need stands for explanation. It will not do to ignore it, and rationality demands good apologetics in favor of the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar, and skepticism directed towards the missing papyrus theory.

“As it stands now, the anti-Mormons have the upper hand, only because the apologists have focused on where the most fertile ground is, and have not dealt with the real “icky” stuff where the greatest need stands for explanation.”

Sorta like the drunk looking for his car keys under the street light, because it’s easier to see there.

Thomas, I’m not comfortable with the analogy you have just made. We have good people at FARMS doing the best they can. They are not like drunks. They just have an established paradigm.

Author

Re 27 Douglas

Yeah, I agree. I think we’re saying the same thing here. What I meant is that JFS was drawing conclusions that he perhaps thought he was safe in making (believing science would not ever be able to conclusively show how old the earth was, though I admit it would be foolish for him to conclude this given his contemporary Eyring). In this exact instance, I think you’re right, that science was unaffected by JFS’s belief. But this is a measure of scale and not necessarily a general rule. Consider the many scientists and their propagation of the idea of a heliocentric solar system. I think we could make a case that science as a field was hindered (erroneously) in this case. So while I do believe they should/could occupy separate domains (I view them as tools in a toolbox), I think there is often some erroneous overlap. But many would argue that erroneous beliefs, if they make you happy, are perfectly valid.

I think you’re absolutely right. Not sure what causes this, except that in my own theory (again the different tool theory), people are simply using the wrong tools for the job. Personally (not to derail the discussion here) but I think this is closely connected with faith. When faith becomes insistence on things that seem very implausible we make the mistakes of insisting on a global deluge. And yet, faith is what we celebrate, revere, and seek.

Author

Re #31 ST

You know I actually think this is a great point. I hate labels, and I admit I have been labeling horribly throughout this thread. I do believe that the FARMS folks are good people. I know many of them are smarter than me, better educated than me, and certainly within their domain, I am not even in the same ball park. I recognize this, and try to remember this when painting with a broad brush.

For me, it’s like Hawkgrrrl said – following the evidence is what I consider the hallmark of a good scientist/truth-seeker. I know this is the ideal, and doesn’t always happen (everyone has an agenda). But often the apologist route seems to be backward – know the truth, find the supporting evidence, and dismiss contradictory evidence. Personally, I feel like Widstoe (and Roberts, and Talmage) was not in that camp (though I could be sorely mistaken). But modern apologist writings give me the impression that they are in that camp and hence have it backward. Therefore, when I read their writing I often come away feeling intellectually cheated!

Author

Re #29 ST

Thanks, ST, I honestly feel like I better understand your point of view now. I’m glad there are apologists like you to counter the less “rational” ones.

However, for me, this is where I get into difficulty. The problem here is that the apologist will continue to search for a way to verify what he/she already knows to be truth. I think the search is great, and shouldn’t cease. But from an information theory perspective, there is information in the fact that the most reasonable explanations end up not working out. Now, there is always the proverbial Black Swan that is the gamechanger. But again, there is information in the fact that many MANY of the things Joseph did would have to be the proverbial Black Swan. At some point, when we incorporate the new information into our confidence distribution, it becomes less likely that there is another explanation that will verify our perceived truth. But apologists will not cede this. Hence there will always be another door. And this same mechanism (not ceding our perceived truth) is the same one that keeps people believing the earth is flat, that there was a global deluge, etc. etc.

Now, don’t misunderstand me, I’m not for one second advocating that we cease searching when we think we have something “figured out.” But, deciding in which basket to place our proverbial eggs, some will better than others.

jmb275,

As professor Faulconer of BYU says, in the impoverished region of life of science it is appropriate to be entirely reductionist when gathering evidence and coming to a scientific conclusion. The problem here is that we are not in an impoverished region. From a purely scientific or historical perspective, you would be correct.

We are dealing with a mixed bag of regions of life that overlap here. In a faith centered region of life, in which apologetics rules, we have multiple sources from where we can draw truth. The Holy Ghost is our primary region for fundamental truth of faith. Therefore, it is NOT correctly following the evidence in the religious region of life to let the impoverished region of science rule outside its bounds. Science tells us nothing when it comes to the fundamental truth of religion. So, since testimony is our primary evidence, it leads our FINAL conclusion.

Where the methodology of most apologists is flawed is to not let SCIENCE SPEAK FIRST and THEN come to a religious conclusion afterward. But in the apologetic region, science only has so much weight. It has something to say, but it isn’t primary evidence. However, when tradition or paradigm contradicts science or other evidence, apologists should tread very carefully. That doesn’t mean they come to the same conclusion that the science or the history comes to. It just means that they need to be very careful how they weigh the various evidences. Ultimately, we are making the conscious choice to subjectively let our faith rule. But that is because our trust in the Holy Ghost outweighs all else. We don’t see this as a flaw.

Now, in the Universalist New Order Mormon world, this is a different ball game for some of you. That is because, some of you are cultural Mormons and have no faith in Mormonism. You may have faith in God, but you have reconstructed your faith based on different pillars. That is not to find fault with what you are, but I would ask the same respect from you for my point of view. I know all the problems with historicity. I know all the controversies. Why do I still have a simple faith, and I’m not NOM? I don’t have an answer to that question, but I reacted differently than many NOM types when confronted with these things. I look at it all as the need to get to the bottom of the question rather than concluding that something is false and I have to reconstruct my fundamental faith. The reconstructions in my faith have always been in the periphery, not at the core. EXPERIENCE has shown me that when I dig far enough, I will find that Joseph Smith was right on things that really matter, and that the fundamental claims are real. That doesn’t make it any less complex than it is. I can’t tell you why I’m this way, but I’m telling you that I have a very simple faith in Joseph Smith and in the Book of Mormon to the point where whatever complexity I have ever faced has always just been a puzzle that needs to be solved, not an indicator that something is false.

Oh, and there is one more thing. Too often also, people who have nothing invested in a certain point of view, or who put no stock in core testimony, are willing to let science guide them to a final conclusion, when science has never been about final conclusions. Science is about falsifiability of claims. But science is always falsifying its own beloved claims. Climate change, however beloved, has not been falsified, but it is in trouble. And for any rational person to deny that it is in trouble is not being objective. But having a testimony does not allow me to be objective in final conclusions. That is just the nature of the beast. The Holy Ghost already told me how it is on things that really matter. I make no apology. And this means that I have patience with science and allow science to be the tentative beast that it is. Those that proclaim that the Book of Mormon is not historical for this or that thing that has not been found have too much confidence in science. Because experience has shown that the Book of Mormon is gaining ground, not losing ground. That is because the data set for Book of Mormon archaeology is a growing dataset. And I refuse to be disturbed when I have all the evidences that have already been found just because some things have not. It is inappropriate for me to be disturbed, because science has not falsified the Book of Mormon. In other words, science never proves anything to be true. It can only falsify things. And lack of evidence does not falsify something. It certainly doesn’t uphold it if there is no evidence for it. But it ABSOLUTELY DOES NOT falsify it when there is no evidence found. THAT MUCH IS CERTAIN.

#31 SkepTheist: “We have good people at FARMS doing the best they can. They are not like drunks. They just have an established paradigm.”

And gays are not pedophiles. But that’s not the point.

Have you ever been in a discussion, defending the Church’s position on authentic sexuality, where the other guy says, basically, that restraints on homosexual behavior must be invalid because the desire to engage in that behavior may be somehow innate? And you answer back that all kinds of sexual preferences may be innate, including preferences that even the most liberal-minded must disapprove of, and so whether a preference is innate or not is irrelevant to its morality?

That’s where the guy typically accuses you of comparing gays to pedophiles, or whatever deviant sexuality you were foolish enough to specify. (That’s why I don’t specify any particular preference.) But of course you’re not. You’re taking his faulty analogy, and applying it to a circumstance where even he has to acknowledge that it doesn’t work.

That’s what I did. I’m not calling the FARMS gentlemen drunks, heaven forbid. But the “established paradigm” many of them embrace — find an answer rather than seeking the true answer — is just as flawed as the key-seeking drunk in the old saying about the street light. Nobody risks his child’s life on the frozen Wyoming plains over a “plausible” religion. I believe that for many people, authentic faith according to a “rational theology” reconstructed from the ground up with as many true principles as can be found in our heritage, serves better than a religious practice that requires too many denials of what one is genuinely convinced to be true.

You said “As it stands now, the anti-Mormons have the upper hand, only because the apologists have focused on where the most fertile ground is, and have not dealt with the real “icky” stuff where the greatest need stands for explanation. It will not do to ignore it, and rationality demands good apologetics in favor of the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar, and skepticism directed towards the missing papyrus theory.” Maybe you don’t like the drunk-under-the-street-light analogy, but you said essentially the same thing — just more nicely.

“Ultimately, we are making the conscious choice to subjectively let our faith rule. But that is because our trust in the Holy Ghost outweighs all else. We don’t see this as a flaw.”

It isn’t. The question, though, is not the infallibility of the Holy Ghost, but rather our ability to identify and interpret His communications. “God when he makes the prophet does not unmake the man. He leaves all his faculties in the natural state, to enable him to judge of his inspirations, whether they be of divine original or no. When he illuminates the mind with supernatural light, he does not extinguish that which is natural. If he would have us assent to the truth of any proposition, he either evidences that truth by the usual methods of natural reason, or else makes it known to be a truth which he would have us assent to by his authority, and convinces us that it is from him, by some marks which reason cannot be mistaken in.”

I go back and forth as to whether I envy people with simple faith. I respect your point of view; my aim is to understand it. And I still can’t understand how a person reconciles himself to a “simple faith” which is essentially a presumption that one sectarian doctrine is true, which necessarily means that conflicting doctrines are false. And yet the adherents of those doctrines may also have simple faith in them. I can only trust my simple faith over their simple faith, if I have reason to believe that I am somehow better than they are — better equipped to direct my faith towards the actual, exclusive truth, by a greater ability to recognize and interpret the revelation of the Spirit or otherwise. But if God is no respecter of persons, how can I presume this?

I view faith as a partial synonym for “hope” and “confidence”: I would not call myself a “universalist” (I definitely don’t believe all religions are equally true, which is logically impossible) or say that I “have no faith in Mormonism.” I would rather say that I continue to hold out hope that God will reveal to me — convincing me that the revelation is from him, “by some marks which reason cannot be mistaken in” — that the fundamental claims of Mormon are real. That’s why I’m still here. And I have confidence, based on reason, that if not — if the geographical, temporal, and familial accidents of my birth have not gotten me barking up the wrong sectarian tree — that any God worth seeking is a rewarder, one way or the other, of those who diligently seek him.

Thomas, displaying your lack of respect for them by using an inappropriate analogy was displayed by you, and the inappropriateness of the metaphor remains inappropriate.

No, actually Thomas, the seeking after truth when one has the key to the understanding of truth is not inappropriate. That just happens to go against YOUR own preferred paradigm. But the truth of the matter is, you do the same thing based on whatever bias you have. You confirm your own bias. So the hypocrisy in pointing out their own confirmation bias in your statement is evident. I have lost the ability to be civil now so I’m signing off. The “management” of Mormon Matters has asked me in the past to not display my innate ability to indulge in inappropirate language to display my contempt for other people’s point of view when I lose my temper. Have a good day.

OK, Skeptic. Sorry this makes you lose your temper.

Signing off as — in the words of one of the apologists I’m supposed to show exaggerated “respect,” as if they were rolling on Compton Boulevard — “a cultural Mormon stinking up the place.” Peace.

Skeptic and others, on reflection, I have to recognize that the “drunk under a streetlight” comment goes against my own general rule that fools mock. So while I still disagree with a good many aspects of present apologetic practice, including a frequent lack of respect on their own part, “they do it too” is no excuse, and I ask their pardon and Skeptic’s.

Thomas, keep in mind that you don’t know me, and the lack of respect one person shows to another does not necessarily reflect on groups belonged to or ideologies espoused by someone. I’m a part of FAIR but I do not represent them. I represent myself. I consider them all my colleagues, as well as those at FARMS I consider my colleagues. I am not going to stand idly by and let people trash on them without challenging it. But as you may have noticed, I don’t subscribe to two of their most cherished ideas: a Mesoamerican Cumorah and a missing papyrus. So my lack of patience and control over my temper does not reflect on them. And similarly, their lack of respect similarly does not represent me. Each apologist is an individual too, sons and daughters of God, with families and jobs of our own, just another guy that if you got together and went out to have a burger with or something (since we can’t go have a beer), we are just the same as you. Same feelings, same hopes and aspirations. Please treat us as people and let us try our best to defend what we believe sincerely. If there are flaws in our methodologies, then go about your own business and live your own life, and let us be wrong.

Regarding lack of evidence not falsifying anything,

My doctor wants to schedule me for an angioplasty. I asked him, why doctor? I have no symptoms. My lab tests and EKG are normal. My stress test is normal. He said that absence of evidence doesn’t prove that I don’t have heart disease, so I need an angioplasty.

I decided to get a new doctor, one who knows the distinction between “evidence” and “positive results.”

Re #35 ST

I apologize ST if you feel attacked. My intent is not to attack you. I am merely interested in the topic. You have represented a viewpoint that I am interested in understanding, and I think I understand your position. I respect you for it. I merely disagree. I do hope you don’t feel I’ve disrespected you. If you feel so, I apologize.

I think that without further refining of the semantics and definitions it is fruitless to argue with this. However, I don’t understand because you then say:

So it sounds like you’re not letting science speak first either. I’m confused.

I do not mean to be rude, or challenge you. I don’t know your profession. I know that I’m a scientist/engineer, and I think this a misunderstanding of science. Science does not falsify anything conclusively in real life. It doesn’t prove anything conclusively either. All it does is characterize, and indicate what happens or doesn’t happen most of the time. It’s all a game of probabilities. I could easily disprove Einstein’s equation by conducting a simple experiment and showing that the equation will not hold exactly. Now, it is an unappreciated assumption that noise in the system will be the cause, and that the equation would hold under ideal conditions. The problem is, ideal conditions don’t exist in the real world. So yes, falsifiability is important, as we can show what is unlikely to be the case, but it still will never falsify anything.

For example. I could say “all swans are white.” If you show me a black swan you can falsify my claim. But you cannot show me a black swan. You can show me a swan that you are extremely confident is black, and hence I should conclude that it is most likely true that my hypothesis is false. But you cannot conclusively prove there are black swans. It’s all a game of probabilities.

I think this is an important point because this is the gist of apologetics and science. The swan example is extreme but it’s still a game of probabilities. If you have been told by the Holy Ghost that Joseph’s claims are true, then no matter how many black swans I produce you will hold out that “all swans are white.” At that point, the only real difference between you and me is the threshold at which we decide that perhaps we got it wrong in what the Holy Ghost told us was true.

I have a dog in this fight. I’m BIC Mormon, and I hold a TR. I have faith, albeit a very nuanced faith. Again, I suggest that the only difference between you and me is the thresholds at which we decide to question our base assumptions.

I like what Thomas said.

It is the not the Holy Ghost or faith therein that is the problem. It’s our ability to interpret it properly. My (admittedly minimal) understanding of psychology leads me to question my abilities to properly interpret the promptings.

Again, I hope you don’t feel attacked. I really am interested in understanding, not arguing. I think my elaboration of probability above is useful in helping us see that we’re not that different than each other (as you pointed out).

jmb275,

Sounds like you and me have a lot in common. I’m a fan of Taleb/Black Swan too.

Again, I will try to explain. Donald R. Prothero, a paleontologist, wrote the following:

“As the late Steven Jay Gould pointed out in his book Rock of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, science and religion can be seen as nonoverlapping . . . [W]hen religion tries to interfere with our understanding of the natural world, it overreaches . . .” (Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters, p. xvii)

“Science is not about final truth or “facts”; it is only about continually testing and trying to falsify our hypotheses . . . (ibid., p. 5).

Humans have many systems of understanding and explaining the world besides science . . . That’s fine, as long as they don’t call these ideas “scientific.” . . .” (ibid., pp. 6-7).

“Ontological or metaphysical naturalism . . . makes the bold claim that the natural is all that exists and that there is no supernatural. That is an interesting philosophical issue, but that does not reflect what scientists are doing. Instead, scientists practice methodological naturalism, where they use naturalistic assumptions to understand the world, but make no philosophical commitment as to whether the supernatural exists or not. Scientists don’t exclude God from their hypotheses because they are inherently atheistic or unwilling to consider the existence of God; they simply do not consider supernatural events in their hypotheses. Why not? Because, . . . once you introduce the supernatural to a scientific hypothesis, there is no way to falsify or test it. We might want to say, “It is this way because God willed it so” . . . But scientists are not allowed to do this, because it is completely untestable and therefore outside the realm of science.” (ibid., pp. 10-11).

Apologetics is a religious thing, and we are really talking about religion in the end, not science. I’m saying frankly that a rationally religious conclusion simply trumps everything else, period, for an apologist, because that is the conclusion he comes to based on his assumption that a religious source of information, the Holy Ghost, is the primary source of information around which we interpret everything else, including the science. That doesn’t mean we call the interpretation we come up with this way science.

I’m saying that we allow the science to speak and come to its own conclusion independently. THEN we make a religious conclusion that takes into account what the science said. The science weighs in on the conclusion, but does not determine it. Just because science said what it said doesn’t guarantee that our religious interpretation of the facts will come to the same conclusion. Because, science has nothing to say about religious things, with the exception of when religion makes claims that are scientifically testable. Since the Holy Ghost is a source of information outside the realm of science, and in the realm of religion only.

I never said a religious thing was scientific. I said a religious conclusion interprets the science, but does not claim to be scientific. I’m saying that an apologist uses science in his conclusion, but his conclusion is not entirely based on what science has to say, and won’t necessarily come to the same conclusion that the science came to.

Does this help?

Oh and also, I agree with the subjectivity of interpreting what the Holy Ghost has to say, but the apologist has nothing but his own subjective interpretations to go off of, and must, of necessity, have skepticism in the claims of revelation of other people that contradicts what he has received himself about what the Holy Ghost has to say. Thankfully, I’m not a lone person in this. There are quite a few TBMs out there with the same fundamental testimony I have of the historicity of the Book of Mormon and the fundamental claims of Joseph Smith, and the fundamental claim that Thomas S. Monson is his true successor. I am very nuanced in my faith on issues on the periphery. The core claims are not negotiable for me, and I treat with skepticism any claim to the contrary, including Universalist NOM claims that the Church does not have an exclusive mission in the world to have a special kind of authority.

jmb275,

One more thing. I don’t think that I disagree with anything you said regarding falsifiability. I think that you have restated what I was trying to say in a more nuanced way. I never meant to say that anything was conclusively falsified by science, and I agree it is all probabilistic.

The main problem with Stephen Jay Gould’s concept of science and religion operating with “non-overlapping magisteria” is (as Richard Dawkins — with whom I generally disagree — argued) the line between science’s and religion’s respective turf isn’t defined. Most traditional religions don’t just concern themselves with the scientifically unanswerable questions about First Principles, such as the existence and nature of God and his relationship with humanity; they also state, as doctrine, matters of asserted historical fact that in other contexts would be accessible to empirical or rational inquiry. The example Dawkins gave was the Catholic doctrine of the Assumption of Mary: It is a matter of historical fact as to whether Mary was physically taken into heaven, or whether her body decomposed on the earth after she died.

That’s a fair point — sort of. Realistically, though, the question of what happened to a body of an obscure Galilean woman in first-century Judaea is just not accessible to human inquiry, barring some kind of time-travel technology, which is unlikely. As a practical matter, the Assumption of Mary is as immune from the inquiries of science as is the existence of God.

History is not a “science” — or at least, not as much of a science as basic physics or chemistry, where the probabilities are so much more solid that you can be confident that every time you combine materials in the right proportions, something goes reliably “boom”. And yet it uses aspects of the scientific method — evidence and verification. To the extent historical methodology is used in litigation, in establishing who did what to whom, good Mormons serving on juries accept the “science” of evidence with enough confidence to hang men, ruin them or deprive them of their children. I am just not able to assent to do this in one context, but set the methods of history aside in another. It is one thing to walk by faith into areas where science is definitionally incompetent (as with metaphysics) or practically so (as with events presumably lost to history). It is another thing to refuse to accept the verdict of evidence that would convince me in a less emotionally charged context, or to pretend that the evidence is more ambiguous than it really is.

You said “[T]he Holy Ghost is a source of information outside the realm of science, and in the realm of religion only.” Yes. But what of occasions where a person decides the Holy Ghost has imparted information that is accessible to the methods of science? Over at FAIR, the rhetorical cannons have blasted away at Ron Meldrum and his North American theory of Book of Mormon geology, which conflicts with the Mesoamerican limited-geography model favored by the majority. Mr. Meldrum has indicated that he believes that the Spirit guided him to his conclusions about Book of Mormon geography. I’ve heard other members testify tearfully about how the Fall River skeleton, or other artifact, is evidence for the Book of Mormon. I have not yet been convinced that most people are able to distinguish genuine revelation by the Holy Spirit with what Locke called “enthusiasm,” which (because it leads to mutually incompatible sectarian conclusions) is not a reliable means to true knowledge. In short, reason is fallible, but the process by which revelation interacts with our understanding is also.

I believe that I am justified, when I experience something that strikes me as outside the realm of ordinary emotional experience, in considering that this may be a genuine communication from the Holy Spirit, independent of my natural mind. If what that experience inclines me to conclude is not contradicted by one of the other means the Lord has provided for obtaining knowledge, then I believe I am justified in choosing to hold fast to belief that it is a genuine revelation.

SkepticTheist #46:

“Oh and also, I agree with the subjectivity of interpreting what the Holy Ghost has to say, but the apologist has nothing but his own subjective interpretations to go off of, and must, of necessity, have skepticism in the claims of revelation of other people that contradicts what he has received himself about what the Holy Ghost has to say.”

Why “must” he have such skepticism of others’ claims? He “must” elevate his own subjective interpretations above others’, only if he hase some reason to believe that his subjective intuition is superior to others’. Why should he not presume that, all things being equal, one man’s capacity to draw correct conclusions from subjective experience is as good as another’s? Why is that presumption not required either religiously (“God is no respecter of persons”) or biologically (with some minor variations, our brains are physically identical)?

One thing my experience demonstrates to me, is that the emotional temperature in any debate is in direct proportion to the degree to which the participants’ positions rest on subjective considerations. People tend not to get angry when their reasoned arguments are met with reasoned counterarguments. They get angry when the other guy cuts too close to the point where all of our arguments ultimately rest on unexamined first principles. Because when someone questions what we know by intuition, he hasn’t just overlooked a relevant fact, or forgotten to carry the two. He’s attacking us — denying our belief that we are uniquely well-equipped to just know what everybody simply must know, deep down inside, because we do. He’s telling us that we’re just not that special.

I used to get into political discussions with a liberal lawyer at a previous firm. You could always tell when he’d run out of logical ammunition: He’d say “Oh, come on! You can’t seriously believe that! Same thing when I challenge a global-warming alarmist who doesn’t know black-body radiation from the Black-Eyed Peas or feedbacks from feedbags. It’s only a matter of time before I get compared to a Holocaust denier.

My feelings of peace taking the Sacrament might be a witness that the Church is the only true and living church on the face of the whole earth, and that every teaching professed by the Church is the literal truth, from the reality of the Great Apostasy to the literal antiquity of the source of the Book of Abraham on up. I have no way of knowing what it was that Jonathan Edwards described as his conversion experience (in the course of which he came to love the harsh predestinarianism of his Calvinist tradition, which conflicts sharply with Mormon teaching), and yet aspects of it sound very similar to things I have felt, or what I hear described in testimony meeting or Joseph Smith-History in the Pearl of Great Price. Maybe Edwards was feeling the real thing, and TULIP Calvinism is the true gospel.

Alternatively, maybe both Edwards and I would be more justified in construing what we experienced, simply as a confirmation that God approves of our spiritual course, and that continuing in the direction we are headed will lead to further light and knowledge.

If I can poach onto Elder Uchtdorf’s domain of aviation analogies, the Spirit has always seemed to me to work more like ADF that GPS. With a GPS receiver, you can confirm exactly where you are, as well as where your destination is. With the more primitive ADF, all you know is the direction of the beacon that sends out the directional radio signal. You don’t know exactly where you are, but you know how close you are to the heading you need to be following, and how much you need to alter your course.

GPS spirituality presents much more potential for conflict. It doesn’t just call people to repentance, or give them assurance that they are heading in the right direction. Instead, it tempts people to claim divine sanction to matters on which equally conscientious people, believing themselves equally inspired, disagree. I believe that something that can tempt good people to be angry with each other, cannot be wholly divine.

Thomas,

I’m very uncomfortable with even responding to this because I know where this is going. As Richard Bushman writes:

“At Harvard in those days, we talked a lot about the masses, envisioning a sea of workers’ faces marching into the factory. Tracting in Halifax, we missionaries met the masses every day and they didn’t exist. There were a great number of individual persons . . . That realization planted a seed of doubt about formal conceptions. Did they conform to the reality of actual experience? . . . This skepticism grew, especially after I entered graduate school . . . To confuse intellectual constructions with reality . . . came to seem more and more foolhardy . . . I was depreciating intellectual activity rather than decrying it . . . Paradoxically, in my own intellectual endeavors, I have benefited from this skepticism . . . , for it has led me to trust my own perceptions and experience over the convictions of my fellow historians . . . However fallible I might be myself, . . . I had to trust my own perceptions over everything else.” (Believing History: Latter-day Saint Essays, pp. 22-23.)

Its not superiority. Its that I follow what the Holy Ghost tells me personally, and I have no choice but to view with skepticism what another person thinks that contradicts that. The Holy Ghost leaves me no choice, because he has not chosen to give any other sign aside from what Moroni tells us he does, to prove anything to anybody. To have faith in my own personal perceptions of what the Holy Ghost tells me is to automatically view with skepticism anything else. That’s just how it is. There is nothing else. Any time faith is exercised, skepticism is exercised in the opposite direction. The two go together in a package.

And for someone to explain away my experiences in their own mind is their own prerogative. I don’t play games when it comes to my testimony. It is what it is, and I accept it with simple faith. There is nothing more and nothing less than that. If you view that differently, then you are doing the same thing I’m doing. You are applying skepticism to my claim. And so, that’s about it… There is nothing I can do for you, nor you for me. The very fact that you have an issue with what I say is because you are using skepticism directed towards my claim, because you don’t BELIEVE it.

I grant that the Spirit will take people in other directions for their preparatory stages before coming to ultimate truth, but I must view with skepticism a greater truth on the earth as Mormonism. Mormonism is not superior. It just has a mission that other Churches do not have. I have no reason to conclude that any other person’s perception of truth in what they believe outside of Mormonism is as a result of either (1) having been deceived to leave Mormonism and having lost the light he may have had before, or (2) being in a preparatory stage where it is not his time to accept the truth yet, and the Spirit will not reveal it until the time comes.

So on this point, it is what it is. Please don’t accuse me of a superiority complex or attitude, because you know that isn’t true. I have to draw a line in the sand somewhere, so just let it be and accept that I believe differently than you.

I always say to people to get a testimony that God wants them to be in Mormonism, not that it is true, if they have issues with it being true. That isn’t the point.

Be aware that you have dragged me into this particular point kicking and screaming knowing that this statement I have just made on this NOM dominated site is bound to have others come and try to oppose my point of view on this point, and if that is what happens, I promise you I’m done on this thread. Let it be what it is. We disagree on this point.

Oh by the way Thomas, you bring up Rod Meldrum. My name is Edwin Goble. I am the author of This Land: Zarahemla and the Nephite Nation. Rod Meldrum’s theory is not his own. It is MINE. He based his work on MY BOOK. I am the author and originator of the heartland geography. I RETRACTED it because it is wrong. Period. The Spirit has led me in a different direction now, because I know MY theory is WRONG, after having had further spiritual development since I wrote that book. I never claimed inspiration for that book, only that I felt good about it at the time, and Rod Meldrum is misled, as well as anyone else that subscribes to the Heartland theory and claims revelation for it.

“I always say to people to get a testimony that God wants them to be in Mormonism, not that it is true, if they have issues with it being true.”

I think that’s excellent counsel. Would that people who followed it were not looked down upon by so many of their fellow Saints.

If I dragged you anywhere kicking and screaming, recognize that what set me off your statement that a group of people which I took to include me “have no faith in Mormonism.” I have faith that God wants me to be in Mormonism. By the standard you just referenced, that ought to be enough. I wish I had understood earlier that this was your belief.